Define Curvy

This is a post about why it is so hard to design for and fit female bodies. It includes a lot of questions for which I don’t have answers, but I find it helpful to think through and talk about these issues.

I chose the Remy Raglan by Sew House Seven for an upcoming class on making tops. I like raglan styles and they are easy to sew. I also like Sew House Seven patterns. I’ve made myself three or four Toaster Sweaters and I also like the Free Range Slacks. SHS has a comprehensive sizing guide on their website. I’m not laying any blame on them; rather, this post is to highlight how designers have choices to make and their choices impact the process of making one’s own garments.

Sew House Seven patterns come in a wide size range, and most come in both “standard” and “curvy.” If you look at the sizing guide on their website, Sew House Seven notes that:

There are differences between the Curvy and Standard sizes 16 -20. The shoulders on the Curvy sizes are narrower, the cups are fuller, and the tummy and hips are rounder than the Standard sizes. The Standard sizes grade slightly in height and the Curvy sizes do not grade in height.

Patterns typically are drafted for a body that is 5'6" tall and wears a B cup. Any deviations from those norms require adjustments to the pattern. I am 5'7" tall, which doesn’t seem like a huge variation, but I have a longer-than-average torso. I have to lengthen tops by 2-3". And I do not wear a B cup. I almost always have to do a full bust adjustment of some sort or use my sloper, which has bust darts incorporated into it.

For some reason, the words “standard” and “curvy” trip me up. I think my body is “curvy” in the traditional sense. My bust and hip measurements are almost identical. My waist measurement is 7" less than my bust and hip measurement. I can’t find a specific reference, but I remember reading somewhere that an hourglass shape is defined by a waist measurement that is 10" less than bust/hip, so I’m close, but not quite there.

I don’t think my definition of curvy lines up with the Sew House Seven definition of curvy, however. Looking at their fit guide, I believe their definition of curvy lines up better with women who have pear-shaped bodies and carry most of their weight in their tummy and hips.

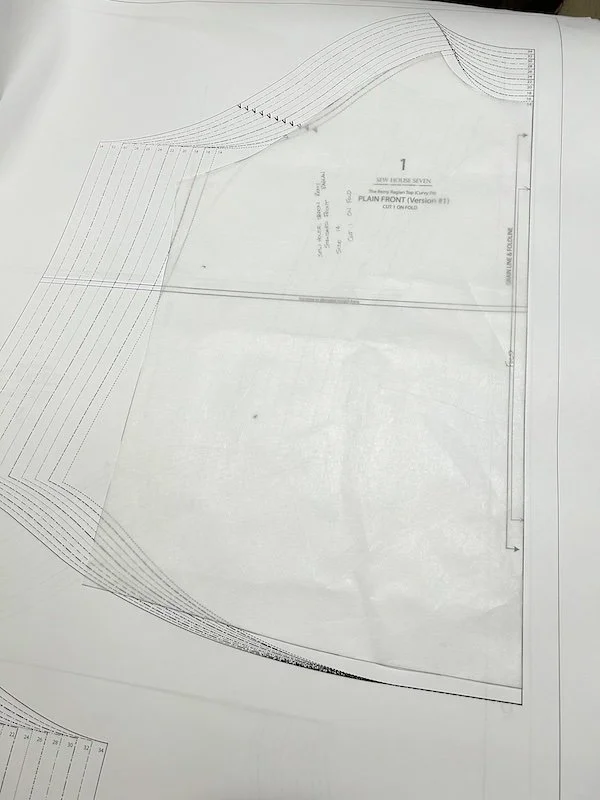

It’s a bit hard to see in this photo, but I laid the standard pattern piece for the size I made over the same size in the curvy version.

I noticed immediately that the standard pattern piece flares less below the armscye than the curvy piece does. The curvy piece also has slightly narrower shoulders, and that was the biggest clue for me that I needed the standard pattern piece. I have broad shoulders and have to adjust that area on many patterns.

That decision out of the way, I made a muslin out of an old linen sheet to check the fit. Except for the length—more on that in a moment—I nailed it out of the gate. The upper bodice fit well and I was able to move my arms and shoulders without binding.

I went ahead and made the store sample out of some Kaffe cotton sateen. I made it in the size I had chosen without a length adjustment. If I am making a store sample for a class, I try to make it exactly according to the pattern, without any adjustments for my body. And this is what it looked like when I put it on:

Is this a fabrication problem or a fitting problem? I don’t think it’s a fabrication problem—I’ve used this cotton sateen enough to know that it drapes nicely. The Remy pattern does make the point, several times, that sewists should choose a very drapey fabric because a stiffer fabric won’t hang as nicely. This is a fitting problem, and here it is in a nutshell:

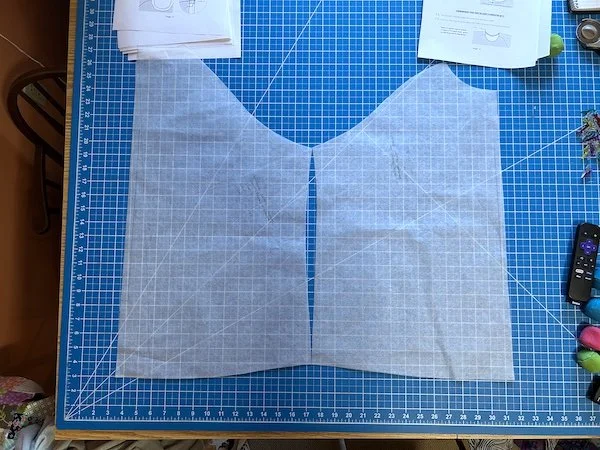

These are the front and back pattern pieces for the Remy, laid side by side along the side seams. What do you notice? The front length, which is on the right side of the right pattern piece, along the fold, is exactly the same as the back length. That’s fine if you’re flat chested. If you have any kind of bust fullness—and I would argue even a B cup amount of fullness—the front isn’t going to be long enough to go over it. If you have a fair bit of fullness there, as I do, the front definitely isn’t going to be long enough to go over it. The front of the top rides up as a result. I almost always see some additional length in the front pattern piece of most patterns and was surprised not to see it here. I suspect this is the reason for the emphasis on using a drapey fabric. This problem was less evident in the muslin version I made using the old linen sheet, but it was still present. I also haven’t done the same front/back comparison on the Curvy pattern pieces, but I’d be willing to bet that they account for this issue.

There are two fixes for this, which come down to making a full bust adjustment of some sort:

1) Redraft the front curve so that it is lower than the curve on the back and provides the extra length that is being taken up in the bust.

2) Add bust darts.

The first fix is easier than the second. I don’t see a lot of raglan patterns with bust darts. I did find a couple of tutorials on adding bust darts to raglans, though, and I don’t think it’s overly difficult. I haven’t decided which method I am going to try. Either way, I will begin by lengthening the pattern pieces by at least 2".

Some days, I wonder if I need my head examined for trying to teach garment classes. I am much better about seeing problems and knowing how to fix them than I was a few years ago, but “solving for X” isn’t easy when X could be one of many variables or even a combination of several variables. (I’m looking at the raglan sleeves in that photo of me, above, and wondering if I need to adjust those, too, or if that’s a side effect of trying to take a selfie in the bathroom.) The feeling of satisfaction when you nail the adjustments and get a flattering garment is worth the effort, but you have to kiss a lot of frogs to find that prince.